The previous webinar/blog discussed the connections between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and changes in the brain and body, how they impact child development which then leads to greater risk of victimization and perpetration. The topic is rather complicated and heavy, and there were a lot of good questions after the talk, but I thought I’d spend this time on the more hopeful topic of resilience and recovery. Here is the link to the recorded webinar on 31 August.

Our brains have a certain amount of plasticity throughout our lives. That makes them vulnerable to negative environmental influences, but it also makes them resilient and open to positive influences, which is what I’ll be discussing today. “A healthy brain architecture provides the basis for good self-esteem, and a locus of control for effective self-regulation, not only of behavior but also of the physiological responses to stressors that are regulated by the central and peripheral nervous systems.” (1). This is the foundation of resilience. Like trauma, it resides in our brain and bodies, and not necessarily in the events we experience.

What is important to understand is that we are designed to adapt to our environment, whether it is positive and encouraging or negative and harmful. In this way, people who have survived horrific trauma in their past now struggle with behaviors that kept them alive during that time but now are maladaptive in their new and safe environment. We can therefore say that they are resilient and strong people because they adapted to their dangerous environment and survived.

“If you feel safe and loved, your brain becomes specialized in exploration, play, and cooperation; if you are frightened and unwanted, it specializes in managing feelings of fear and abandonment.” (2)

What do we mean by resilience? Most people think of resilience as having a positive outcome after adversity. There is also posttraumatic growth, which is positive development and even thriving in the aftermath of traumatic experiences and that the stress itself is the catalyst for these changes. Resilience is also protective to the effects of trauma before the event when coping mechanisms are operating at the time of the event.

Resilience doesn’t mean that our brains revert to the way that they were or would have been. The neural connections as well as some of the architecture has been altered, even if the function seems to be normal. This is an example of our brains’ amazing plasticity. No matter what kind of physical or psychological trauma we experience, there are always marks, and the events are part of our story. Our behaviors may have recovered from their maladaptive patterns, but some of the gene expressions may have not.

Scientific literature describes neuro-biological factors that appear to influence resilience, such as genetic and epigenetic factors, neurochemical systems, and the connectivity of specific neural networks. As with the consequences of trauma, the mechanisms that build resilience are also complex and are influenced by a variety of internal and external individual characteristics. We are only beginning to understand these interactions on a neurobiological level.

“The brain is the central organ of stress and adaptation to stressors because it perceives what is potentially threatening and determines the behavioral and physiological responses.” (1)

Levine (3) states that “Trauma resides in the nervous system and not in the event itself.” How you and your nervous system responds to the traumatic stress determines the trauma symptoms. This is part of the reason why different people who experience the same event experience different symptoms and responses to it.

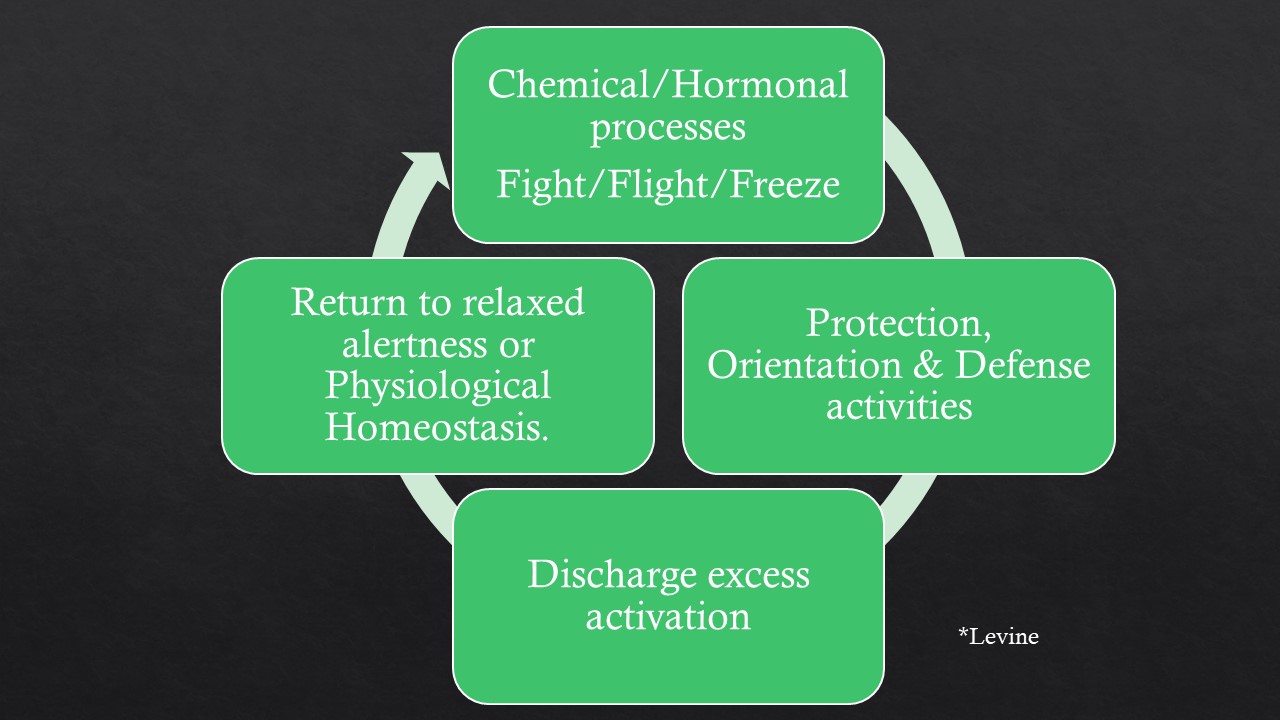

Levine explains the physiological mechanisms for self-protection that help respond to and defend against trauma: 1) Chemical and hormonal programs are engaged (that is our fight/flight/freeze responses), 2) energizing the activities of protection, orientation, and defense (whatever we can do to fight or protect ourselves in the moment), then 3) discharging the excess activation (or sympathetic energy), and 4) returning to a relaxed alertness or physiological homeostasis. (3) When this cycle is disrupted, then the likelihood of suffering traumatic symptoms is greater. Resilience and employing coping mechanisms means that we have a better chance of allowing this cycle to continue and resolve.

Here’s a story to help narrate this concept. A few years ago, I was trail running alone in Colorado. As I came down a pass there was a huge flock of sheep being guarded by a couple of Great Pyrenees – huge dogs! I didn’t know what to do so I just slowed to a walk to go through. The dogs would have none of that. They came up and barked and snagged my clothes and tore through my legs. I thought I was going to be mauled, perhaps killed! But I didn’t scream, I didn’t run. I just kept praying to Jesus that he would call his dogs off! They didn’t rip my legs to shreds fortunately, and finally they relented, but stayed very near me. I sat down and waited. And they watched me until they walked away, and the sheep followed them. I finally got down to where my friend was and then I could relate what happened to me and get care in an emergency clinic. I even had enough presence of mind to tell the doctor that he wasn’t cleaning my wounds properly – at least he complied and I didn’t get an infection. When I got back to their house, I wasn’t even afraid of their Golden Labrador.

That some people experience terrifying events and yet come out relatively unscathed has to do with their present resilience factors. Factors such as having stable attachment relationships and people with whom to process an event. Another is their ability to regulate themselves and their emotions such that they are able to “keep their head”, that is to maintain connection to their frontal lobes that handle executive functions in the face of fear and adversity.

Resilience in the context of trauma is as much a matter of the state of the person prior to trauma as it is in posttraumatic recovery. Early life experiences play a key role in the development of the child and either nurture or hinder the development across the various domains (cognitive, physical, emotional, social). These experiences have impacts that are felt throughout the lifespan. The amount as well as consistency of care given are important in facilitating positive resilience factors.

Therefore, ACEs, or lack of them, can make a big difference in posttraumatic recovery. When I consider some of the stories of survivors who are now leaders in anti-trafficking work I wonder if a more robust early childhood helped them through the trafficking experience and facilitated their posttraumatic growth. This contrasts with many women who suffered a lot of childhood adversity prior to being trafficked and have a tougher posttraumatic healing journey. It’s as if they have a deeper hole to climb out of. I’m painting with a broad brush and is only a hypothesis based on my reading and experience. I’d like to see a study about this.

Cultivating resilience prior to trauma is important. Nobody can predict what will happen to us, but adversity is a part of life. These practices can be taught to young children as well as incorporated throughout adulthood. Not all are necessary but focusing on your stronger factors can help shore up the weaker ones. Iamcello et. al. (4) have identified six psychosocial factors that promote resilience in individuals:

1) optimism: maintenance of positive expectancies for important future outcomes,

2) cognitive flexibility: ability to reappraise one’s perception and experience of a traumatic situation instead of being rigid in one’s perception.

3) active coping skills: identifying and utilizing character strengths to act and create resilience.

4) maintaining a supportive social network and having good role models,

5) attending to one’s physical well-being,

6) embracing a personal moral compass: faith, spirituality, or holding a set of core beliefs that are positive about oneself and one’s role in one’s world

Long term voluntary exercise is proven to help boost mood, facilitate better sleep, improve cognition, decrease depression, decrease impulsivity, regulate anxiety, and increased ability to assess and adapt to new environments. (5) Sleep is also very important and has many of the same benefits! Sleep is medicine!

It seems like an obvious factor, but spirituality and faith have been shown to facilitate posttraumatic growth (6). However, negative religious experiences can hinder recovery. It is therefore important to address – but not push – spiritual background when working with a traumatized person. A gentle inquiry to open the door is better than ignoring a potentially important feature of someone’s life. There is also a growing body of literature that cites forgiveness – of oneself as well as others – as an identifiable component of healing.

Lessons from work with former child soldiers Many youths recruited into soldiering come from broken and/or violent families and did not have positive attachment figures as young children. “Reintegration for these youth, therefore, does not involve the return to normalcy, but rather the more difficult challenge of establishing a network of positive relationships where they had been previously absent and, moreover, doing so in the face of the stigma associated with their status as former child combatants.” (7)

Young men returning to their home communities were able to heal partly through going through certain developmental stages of socialization such as marriage, fatherhood, and holding steady income. “Poignantly,” Kerig states, “the sense that despite their pasts they were accepted by their communities emerged as a particularly significant theme in their recovery. Facilitated by their participation in traditional cultural cleansing ceremonies, what the respondents cast off was not their memories of their experiences, but the shame associated with them.” (7) The men were recognized for who they are and not for what they had been forced to do and that played a huge role in their reintegration and recovery.

Ideas & Interventions & Take-home messages

It is axiomatic to say that “if you have worked with one trauma survivor, you have worked with one trauma survivor”. Every individual is different. But we do know enough to outline principles and strategies to help someone in their recovery. The recovery process induces new changes in our epigenome, brain connections and architecture such that the processes, and ultimately our behaviors, are adaptive to new environments.

Safe relationships are KEY! What does it mean to be a safe person? Consistency and clarity are two big concepts in safety… but this is a whole other webinar about trauma-informed care.

Our brains remain malleable throughout our lives. They are of course more malleable as children and young adults but there is no time at which they are set in stone. Adults may have to learn things such as self-soothing and trusting people in a safe relationship that most of us learn as little children. Therefore, we need to extend more grace and patience to people struggling in these areas.

Understanding that the connections between brain and body mean that psychological issues have physiological manifestations and physiological activities impact our psychological well-being. Physical activity is VERY important! Sleep is medicine!

Getting your cognitive/thinking brain more online. Increasing and improving connections with your frontal lobe requires many baby steps for the re-wiring, re-connecting. There are many tools and practices that someone can use to maintain a sense-of-self-in-the-present when faced with new or frightening situations.

The healing happens when we are no longer identified by our trauma.

Basically, these form a short list of general good self-care practices. But easier said than done. As they say, habits are hard to form, but then they are also hard to break.

References

- McEwen BS, Gray JD, Nasca C. Recognizing resilience: Learning from the effects of stress on the brain. Neurobiology of Stress. 1 (2015) 1e11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.09.001

- Van der Kolk B. The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Penguin Books, 2014.

- Levine, P. Trauma through a Child’s Eyes. New York: North Atlantic Books, 2010.

- Iacoviello BM, Charney DS. (2014) Psychosocial facets of resilience: implications for preventing posttrauma psychopathology, treating trauma survivors, and enhancing community resilience, European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5:1, 23970, DOI:10.3402/ejpt.v5.23970.

- Reul J M.H.M., Collins A, Saliba RS, Mifsud KR, Carter SD, Gutierrez-Mecinas M, Qian X, Linthorst ACE. Glucocorticoids, epigenetic control and stress resilience. Neurobiology of Stress 1 (2015) 44e59.

- Schultz T, Schwer Canning S, Eveleigh, E. (2018): Posttraumatic Stress, Posttraumatic Growth, and Religious Coping in Individuals Exiting Sex Trafficking, Journal of Human Trafficking, DOI: 10.1080/23322705.2018.1522924.

- Kerig PK, Wainry C. (2013) Introduction to the Special Issue, Part I: New Research on Trauma, Psychopathology, and Resilience among Child Soldiers around the World, Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 22:7, 685-697, DOI: 10.1080/10926771.2013.817816

Required reading for every human: Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl

Recent Comments