This is the blog version of the recorded webinar on 3 August 2020. Here the link to that YouTube video. Please follow this link to sign up to get these posts and notifications about future webinars and other events.

This post is all about prevention. I’m a pediatrician so naturally this is one of my favorite topics! One of the most important aspects about fighting human trafficking is that it is PREVENTABLE! It be stopped from happening! It is certainly not easy but not impossible. What I hope to do here is demonstrate how much public health principles serve as the foundation of a lot of our work in prevention, advocacy, and research. Human trafficking is a public health issue also because of the impact of the consequences spread far beyond the suffering of the survivor.

As a pediatrician, I know about how unglamorous and uncommercial and relatively unattractive prevention projects are. They are not sexy! Donors and followers want punch and results and heroes! Pediatricians (at least in the USA) make the least amount of money of any specialty mostly because lot of our practice is NOT doing interventions (for which we can charge money) and actively trying to prevent interventions! Prevention can be difficult to quantify because the necessary research studies usually take longer and numbers are more difficult to count and analyze, although it is possible!

Think of other public health initiatives: smoking, seatbelts in cars, not driving intoxicated, etc. Bill Foege (former head of the US CDC) said that “The business of public health is prevention: to make what is acceptable, unacceptable.” Therefore, a public health approach is a good way to “move upstream” and prevent trafficking.

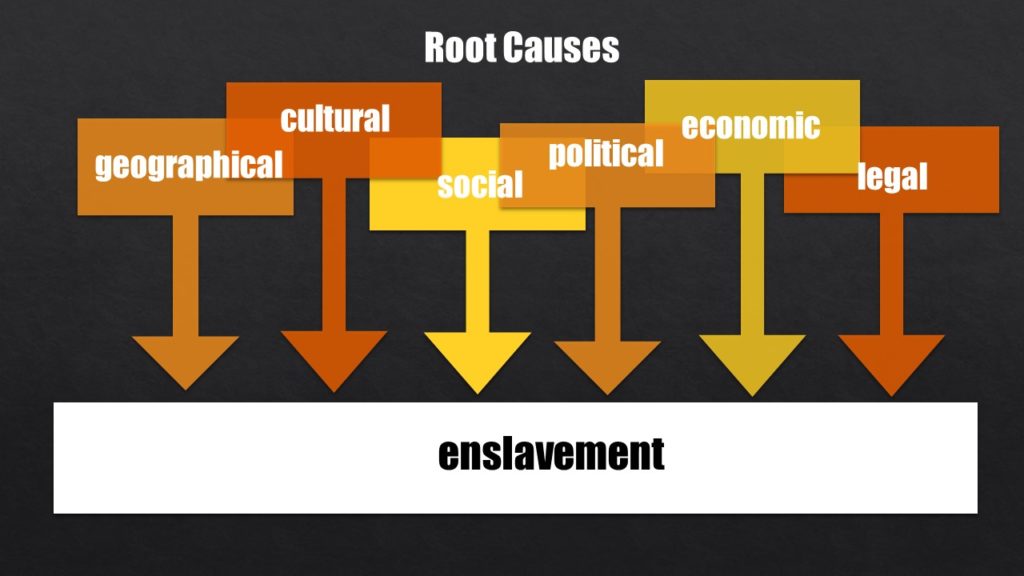

Unfortunately, the anti-trafficking movement got started off mostly on emphasizing a law-enforcement, rescue, and aftercare assistance approach. Not that there is anything wrong with those components – it is important to nab bad guys and help survivors. These problems are seemingly easier to identify and narrow down and therefore seemingly easier to address. However, those types of interventions do not address root causes. We simply cannot rescue or arrest our way out of trafficking.

We simply cannot rescue or arrest our way out of trafficking.

This approach has also formed the framework of the USA State Department’s annual TIP report, which rates countries according to their ability to “prosecute”, “protect” and “prevent”. Although what passes for prevention largely amounts to awareness campaigns or training programs – hardly getting to the root at the problem. “Almost no empirical research was undertaken before Congress adopted the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, formally launching the U.S. government’s effort to combat human trafficking.”1 Therefore, the USA through this report and the political implications of behaving according to these standards have unfortunately broadcasted and recommended a rather narrow approach to addressing human trafficking to the rest of the world and has left us with an under-emphasis on prevention.

I remember when doing anti-human trafficking work was the “cause de la célébrité” in international development (and it still kinda is – Liam Neesom is still getting a lot of traction with his terrible films). Unfortunately, in a rush to do “anti-human trafficking” work, donors stopped funding and workers stopped doing good old-fashioned community development projects, which are exactly the kinds of things that needed to be kept going to prevent vulnerabilities and human trafficking!

There are basically two types of prevention. The first is primary, which is stopping something from happening in the first place. For example, preventing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), helping vulnerable youth stay in school and in families, preventing child marriages, etc. Secondary prevention is stopping something from recurring. Examples of this form include helping someone leave a situation of sexual exploitation/trafficking, criminal deterrence, empowering labor inspectors to identify, report, and abolish forced labor practices, etc.

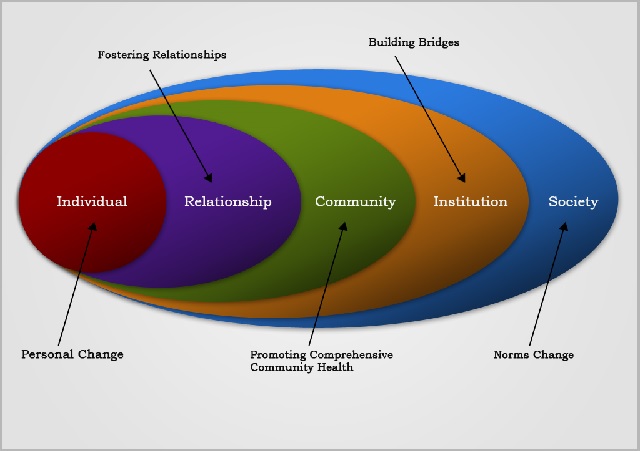

Why is a public health approach appropriate for preventing human trafficking? A public health approach addresses issues at the individual, familial, community, societal and even larger population-based levels.

- Focuses on identifying vulnerabilities that put people at risk for being trafficked.

- Is grounded in research and can provide evidence to building effective interventions. Hopefully interventions that reach people before the traffickers do.

- Can help reshape societal beliefs and practices to change the way we see situations. For example, we moved from the harmful label of “child prostitute” to “at-risk youth” or “sexually exploited youth” and this therefore helped change policies and procedures to assist these youth instead of unfairly criminalizing them.

- Relies on networking, communication, and collaboration. There are too many instances where counter-trafficking orgs have taken a scarcity, zero-sum, get-our-piece-of-the-pie approach. Many have adopted a “we know what’s best” or “we don’t need to continue learning from others” attitude.

- Engages all stakeholders from survivors to service-providers to communities at large.

- Emphasizes evaluation and monitoring practices that ensure that interventions are effective. Sometimes, however, we won’t know if our interventions will work until we start, despite our best preparatory research.

“Monitoring and evaluation components enable policymakers and stakeholders to distinguish between whether they are doing something about a problem or doing something effective.”1 It would be fantastic for donors to insist that programs have demonstrated preliminary research as well as a plan for evaluation and monitoring AND (importantly) fund these efforts. Good examples exist where grass-roots organizations have partnered with academic institutions to produce good research about vulnerabilities and interventions.

“The more governments and communities know about what makes individuals vulnerable, how traffickers operate, and what underlies demand for exploited labor, the better positioned they will be to respond to and prevent such exploitation.”1

What does a public health approach to human trafficking prevention look like? Prevention programs might include the following interventions – this is not an exhaustive list. I’ll also highlight where healthcare professionals (HCPs) can specifically make a difference. The article by Greenbaum2 is also a good reference for how HCPs can prevent human trafficking. Let’s look at some examples of what can be done at the individual, relational, community, and societal leves.

Regarding individual risk factors, healthcare professionals can:

- Provide risk-specific resources or interventions such as intervening to prevent ACEs, screening parents for adversity and mental illness.

- Ensure access to mental health services.

- Advocate for resources and assistance for people with disabilities.

- Screen & Identify sexually exploited, trafficked, pimped youth and adults

- Address LGTBQ-specific risk factors for being exploited.

- Develop an awareness of, and skills in identifying and referring possible incidences of organ trafficking in a patient in need of one, or caring for someone who has donated an organ on suspicious grounds

The general public can provide life skills training, mentoring and other forms of support such as providing access to education, vocational training, employment, housing

The relational level is invested in developing strong interpersonal skills. HCPs (especially Pediatricians!) can:

- Provide anticipatory guidance about healthy sexual relationships

- Discuss pornography and internet safety with patients

- Provide resources in the waiting rooms – ensure a safe environment & their questions are welcome

In general, people can start learning teaching about grooming techniques such as used by “loverboys”, “romeo” pimps in traffickers in schools, online and other youth-centric spaces. Strengthening families and reducing ACEs, and advocating for peer group interactions, mentoring, and tutoring opportunities

At the community level, such as in schools, neighborhoods, and places of worship, HCPs can:

- Train other HCPs at clinic, or hospital about TIP

- Understand the local situation, such as which sectors might be likely to harbor trafficked people, which organizations are working against TIP, etc.?

- Collaborate with orgs and social workers to synergize prevention efforts to learn how and where to make safe referrals

The general public can raise awareness about the problem (locally!). People can also volunteer with a local organization to help in their locally-applicable prevention efforts, such as health issues, identifying families at risk, or identifying other potential sources of exploitation such as is there recruitment for work or study abroad? The public can also work to counter views, behaviors, and practices that foster demand

Societal factors include social and cultural norms, as well as political issues. At this level HCPs can:

- Advocate against and stop crippling medical debt (a big problem in developing countries).

- They can also raise awareness about the general issue. HCPs are usually respected in communities and when we are standing up for a kind of injustice, people will take note.

Generally, people can engage on several different aspects such as

- Policies (social, economic, etc.) such helping migrant agricultural workers with documentation and empower them to receive proper wages

- Better trained and less corrupt labor inspectors

- Criminalizing child marriage

- Requiring age verification to access porn, challenging harmlessness of porn

- Protection of refugees and asylum seekers

There are some potential limitations and pitfalls to prevention work. When an organization or research team sees a problem in a particular way and takes a study approach that seems valid in one perspective but is invalidating in another perspective. For example, when research on the health consequences of sexually exploited women was dominated by studying HIV prevalence and transmission it portrayed the women as vectors of disease and not as whole persons with more complicated health and social histories. This unwittingly created prejudices and stigmatized the women rather than help us understand their situation and how to best help them. Fortunately, we can learn from our mistakes if we are wise enough to listen.

“Healthcare professionals are also encouraged to have influence, where possible, beyond the care of individual patients. Research, health insights, advocacy and promotion of a survivor input enhances the collaborative development of evidence-based approaches to prevention, intervention and aftercare of affected children and families.”3

Most of you are health professionals, but I hope that you can begin to understand just how much health care and its various aspects link to your work against human trafficking. Also, a public health approach is also quite different from a law-enforcement approach to human trafficking.

I want to want to encourage you that you have something to offer in stopping trafficking in human beings! Join a current project or organization or research and try your own ideas, test them, evaluate them, and scale up if they work. Those of you already on the front lines already have rich sources of information regarding some of the most invisible people on the planet. We can work together to help those who have been affected and we can also work together to keep people from being caught up in the first place.

Looking forward to joining you on this journey!

References

- Jonathan Todres. MOVING UPSTREAM: THE MERITS OF A PUBLIC HEALTH LAW APPROACH TO HUMAN TRAFFICKING. 89 N.C. L. REV. 447 (2011) http://ssrn.com/abstract=1742953

- Greenbaum VJ, Titchen K, Walker-Descartes I, Feifer A, Rood CJ, Fong H,. Multi-level prevention of human trafficking: The role of health care professionals. Preventive Medicine 114 (2018) 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.07.006

- Wood LCN. Child modern slavery, trafficking and health: a practical review of factors contributing to children’s vulnerability and the potential impacts of severe exploitation on health. BMJ Paediatrics Open 2020;4:e000327. doi:10.1136/ bmjpo-2018-000327.

Recent Comments